Meet The Exiled Publisher Telling Ethiopia’s Stories From LA

Elias Wondimu never planned on living in Los Angeles. The Ethiopian-born journalist and activist was only visiting the U.S. for a few weeks back in 1994 when some reporter friends in Addis Ababa were arrested, and he realized it wouldn’t be safe to return home.

Wondimu extended his trip indefinitely. He’s spent the past 26 years living in exile, trying to tell stories of Ethiopia and its diaspora that have been censored by the country’s leaders or erased and ignored by Western media.

“The Africa section at your local bookstore is one tiny shelf hiding in the corner,” Wondimu told me on a recent phone call. “It’s supposed to cover an entire continent, 54 different countries, but you’ll find maybe two books on Ethiopia.”

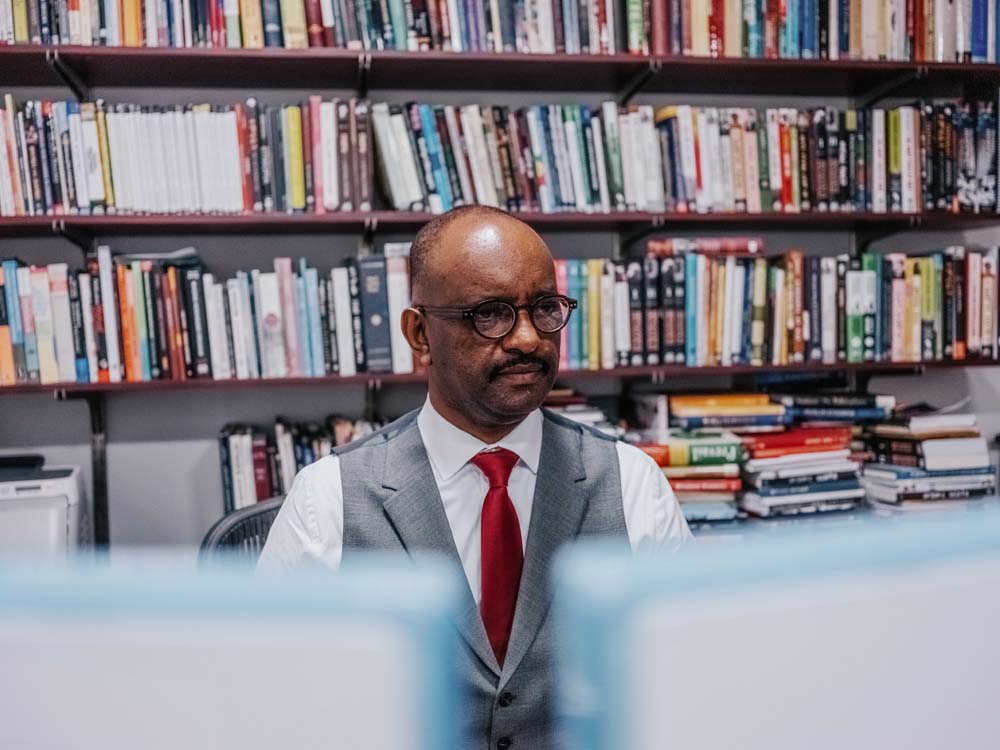

TSEHAI Publishers founder Elias Wondimu at Loyola Marymount University, where his press has been located since 2007. (Chava Sanchez/LAist)

Almost all of the books in circulation about Ethiopia were written by non-Ethiopians, said Wondimu. As the founder of TSEHAI Publishers, an academic press housed at Loyola Marymount University, Wondimu has published nearly 200 books, helping to craft new narratives exploring the politics, culture and history of his diverse homeland.

“I created this press to reverse the brain drain of Africa, to try to reverse the gentrification of stories from the continent, and that’s what we did [at TSEHAI],” Wondimu said. “It was a crazy idea, there was a whole lot of sacrifice, but somebody needed to do it.”

‘AN ACCIDENT THAT SAVED MY LIFE’

Wondimu, 47, didn’t grow up believing the pen was mightier than the sword. He was born in 1973, just a year before the 1974 Marxist junta known as the Derg overthrew the Ethiopian Empire and brought the country under a military dictatorship. Led by Col. Mengistu Haile Mariam, the regime killed and arrested thousands of political rivals.

Wondimu’s childhood was clouded by civil war, famine and the politics of revolution. As a student, Wondimu remembers reading Soviet textbooks and learning more about the Soviet Union and its revolutionary leaders than about his own country’s story. His father, an elected official in Addis Ababa, had always told him to prepare for military service.

In 1991, the Derg was overthrown by guerilla forces who formed a new government known as the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front, which promised democratic reforms but failed to deliver.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The only way to engage in politics or engage the narrative in Ethiopia was to go into the bush and fight and come back again,” said Wondimu. “That’s what the government who took over in 1991 did, and that’s what they challenged us to do. The only solution I saw before me was to go and join the guerilla movement.”

Wondimu got his hands on an automatic weapon and made plans to join a guerilla force in the Bale Mountains south of Addis Ababa, but some friends talked him out of it, urging him to write about his feelings instead.

So, he penned a political essay that was published in one of the Amharic language newspapers in Addis Ababa. Wondimu says when he heard a group of strangers discussing his essay in a taxicab, he realized the power of the media.

“Journalism was not something that I chose,” Wondimu said. “It was an accident that saved my life. I would not have survived had I not been published at that time and found a non-violent outlet.”

Various honors awards hang from the walls of Elias Wondimu’s office in TSEHAI’s Los Angeles headquarters. In 2017, Wondimu received one of the Ethiopian Crown’s most distinguished awards, known as the Grand Officer of the Imperial Order of Emperor Menelik II. (Chava Sanchez/LAist)

That first essay launched his journalism career. Wondimu went on to work as a reporter and columnist at the weekly Moged newspaper in Addis Ababa until he left the country. .

Deeply concerned by government leaders looking to rewrite Ethiopia’s history by destroying culturally significant buildings and natural wonders, Wondimu co-founded the Ethiopian Heritage Trust in 1992, one of the first organizations in his country dedicated to preserving historical sites. He was presenting a paper on that topic at a U.S. academic conference when the Ethiopian government’s press crackdown forced Wondimu into exile.

CONTROLLING THE NARRATIVE

The young exiled journalist chose to settle in South Los Angeles, because that’s where his sister lived.

Los Angeles County is home to as many as 100,000 Ethiopian Americans, according to some estimates: the second-largest population in the country, after Washington, D.C.

L.A.’s Mid-Wilshire District is home to “Little Ethiopia,” a popular concentration of Ethiopian businesses and residents. But Wondimu, who now lives in Westchester, says you’ll find Ethiopians in every corner of Los Angeles.

“Ethiopians live from Bel-Air to Compton, they’re not all segregated in one area,” Wondimu said.

“We can help Africa tell its own stories. The continent has lost so much of its people and resources, but it needs to gain them back, starting with its own narratives.” — Elias Wondimu

Wondimu said L.A. was the hub of Ethiopian diaspora publishing in the 90s. He began working at the Ethiopian Review, then the leading international magazine focused on Ethiopian history and politics published outside of Ethiopia. (He later also took a side job editing a Chicano Studies journal at UCLA.)

During his seven years as the L.A.-based magazine’s managing editor, Wondimu interviewed politicians, scholars and thought leaders, especially exiles, who all told him that their stories were not being published by the press back home, or, for that matter, anywhere else.

“I wanted to change that,” Wondimu said. “I didn’t understand at first that this was a systemic problem in America. I wanted to find a solution.”

Wondimu launched his own publishing house in 1997. He named it TSEHAI after his mother, who had died earlier that year (the name means “the sun” in Amharic, Ethiopia’s native language). A few years later, Wondimu cashed in a 401(k), maxed out two credit cards and took out a personal loan to continue the work full time.

Photographs and art in Wondimu’s office showcase Ethiopia’s diversity and its royal past. (Chava Sanchez/LAist)

Since then, the press has published nearly 200 titles and become one of the world’s leading publishers focused on East Africa. Wondimu has published the accounts of various Ethiopian leaders. n 2012, TSEHAI published the controversial political memoir of former dictator Col. Mengistu Haile Mariam, who was convicted of genocide in Ethiopia but lives exiled in Zimbabwe. Last year, the press put out the latest book by current Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who won the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize last year in part for ending two decades of conflict with neighboring Eritrea.

For too long, Womdimu said, Ethiopia’s leaders have controlled narratives and silenced opposing views. At TSEHAI, he tries to do the opposite.

“To heal history, we have to hear from different corners of the opposing factions,” Wondimu said. “The people should have a right to see that and then make their own decisions.”

Wondimu is one of just a handful of African-born publishers in the U.S. publishing books about Africa.

“Without Elias, many scholars would not have gotten published, and entire generations of knowledge would be lost,” said Wendy Belcher, a professor of African Literature at Princeton who worked with Wondimu at the Ethiopian Review.

ADVERTISEMENT

Wondimu is convinced that, even in the digital age, books, especially those that come out of university presses, remain the core reference materials determining how historical figures and events are characterized in popular culture for years to come.

“Books spur more books, they spur articles and movies,” said Wondimu. “Centuries-old colonial narratives are passed down to new generations. Unless we stand guard against it, those stories will be repeated again in the next round of academic articles, textbooks and documentaries.”

‘WE’VE GOT TO SURVIVE AS A PEOPLE’

Wondimu’s work is now widely recognized in Ethiopia and its diaspora, but it wasn’t always that way. Building a publishing house from scratch, as an exile, was challenging.

Elias Wondimu at TSEHAI’s Los Angeles headquarters. (Chava Sanchez/LAist)

“The guy is a bulldog; he bites and he doesn’t let go,” said Adugnaw Worku, an exiled Ethiopian author whose work Wondimu has published. “He proved all the naysayers wrong. The revolution and government that followed was out to erase the memory of our culture, our history, and create something new. Elias saw that and said, ‘We’ve got to survive as a people.’”

Earlier this year, Wondimu and TSEHAI published Worku’s first English-language book, “The Restless Shepherd,” detailing his remarkable life story, including five decades spent exiled from his homeland.

Wondimu estimates that 65% of the books he publishes deal with Ethiopia, but the publishing house founded various imprints over the years focused on other topics, like the Harriet Tubman Press, created in 2016 to give voice to Black authors and scholars.

After TSEHAI moved its headquarters to Loyola Marymount University in 2007, Wondimu launched the Marymount Institute Press, which publishes books about social justice and spirituality.

“Elias is focused on Africa, but his larger concern is for marginalized people around the world,” said Jeff Dietrich, a founding member of L.A.’s Catholic Worker movement who has published two collections of essays about his work on Skid Row through Marymount Institute Press. “He’s been so supportive of my work and I’m so grateful he’s helped me reach a larger audience.”

RETURNING HOME

Wondimu’s exile from Ethiopia has cost him dearly. He was unable to return home for his mother’s funeral. Because of possible blowback for Wondimu’s work, most of his family had to relocate to Kenya.

Photos of Elias Wondimu meeting various political figures and dignitaries over the years. (Chava Sanchez/LAist)

But Ethiopia’s government has changed in recent years, and so has Wondimu’s relationship with his homeland. In 2018, former Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn resigned from his post and was replaced by Abiy Ahmed, who promised bold reforms.

That July, Prime Minister Abiy visited L.A. as part of the new prime minister’s effort to court exiles in the diaspora. Ahmed called out Wondimu by name inside USC’s Galen Center, recognizing him for his work at TSEHAI and later inviting him to come back home.

Wondimu finally returned to Addis Ababa in September 2018, exactly 24 years after he left as a young journalist. He’s visited six times since, staying for a month or two each time.

Prime Minister Abiy appointed Wondimu to the advisory council for the Ethiopia Diaspora Trust Fund. Wondimu is also partnering with Ethiopia’s National Library in efforts to expand reading culture in the country.

If Wondimu had returned to Addis Ababa as planned back in 1994, he doesn’t think he would have lived to tell his story.

“I’ve seen what they have done to people who challenge their power, and I deal with immense survivor's guilt.”

ADVERTISEMENT

It drives Wondimu to support imprisoned and exiled journalists from abroad, working with organizations like Pen Center USA and the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Wondimu isn’t just publishing Ethiopia’s stories from afar. He says he’s currently working with the Association of University Presses to set up several ‘centers of excellence’ across Africa, providing training and development for local publishers.

“We can help Africa tell its own stories,” Wondimu said. “The continent has lost so much of its people and resources, but it needs to gain them back, starting with its own narratives. Our role in how our indigenous stories are produced and shared, however small it may seem, will shape how we see ourselves and how the world interacts with us.”

Aaron Schrank covers religion, international affairs and the Southern California diaspora under a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation and with support from USC's Annenberg School of Journalism.